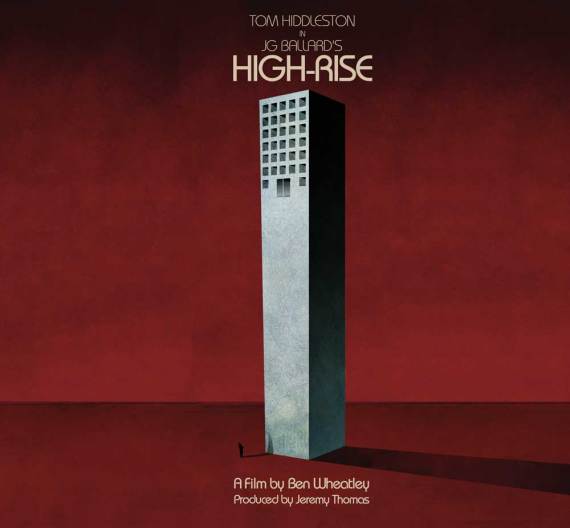

ABOVE: Trailer for High-Rise (2016), directed by Ben Wheatley.

ABOVE: Opening sequence to Shivers (1975), directed by David Cronenberg.

High-Rise, Ben Wheatley’s much-anticipated adaptation of the J.G. Ballard novel, goes on general release in March 2016.

When Mike Holliday reviewed the film for ballardian.com, after it debuted in London, he knew it was a skilful addition to the growing catalogue of Ballard adaptations. Now, the first trailer has been released and the excitement here at Ballardian Towers has hit fever pitch.

The 81-second trailer is designed as an in-narrative advertisement for the film’s main character, the newly opened high-rise, and it looks glorious. The brutalist architecture is as savage as could be expected (the concrete pillar that bisects Laing’s apartment; the massive archways dwarfing the characters), and the sinister imagery is filled with creepy, memorable details (the mirrored lift; the horse in the penthouse; the dog-about-to-be-eaten; the flickering, possessed lighting). Laurie Rose’s cinematography is superb, a fluid, gliding aesthetic that imparts a queasy, restless edge, and the sound design is ominous: the background hum of failing electrical systems and crackling lights.

Another striking detail is the narration. Over a soundtrack of chamber music, it touts the building’s modern conveniences: ‘fully stocked supermarket, swimming pool, spa… there is almost no reason to leave’). The tone is jaded, upper-class, cloying, as if the narrator’s cultured facade hides something sinister below the surface.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

In fact, it is the exact tone used by the narrator of the fake promotional film that begins David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975), which also advertises a newly opened high-rise. Cronenberg’s commercial follows the same pattern, as the stuffy narrator touts the modern conveniences of the Starliner Tower and Apartment building: ‘Relax by the side of our heated Olympic-size swimming pool… It’s all here. A restaurant complete with take-out service. Delicatessen. Variety store…’.

Like Ballard’s High-Rise, the luxurious, high-tech apartment block in Shivers takes care of all its residents’ wants and needs; as in Ballard’s novel, the building possesses a kind of sentience, directly manipulating the behaviour of its inhabitants. Like Wheatley, Cronenberg allows the architecture to dwarf the characters until they lose all traces of humanity. Like the novel, the residents form warring tribes, attacking and slaughtering each other after they are infected by a viral blood lust unleashed by a mad scientist (in Ballard’s case, the mad ‘scientist’ is the architect Royal, who unleashes a brutal architectural experiment on the residents). Common to both works is the odd fact that, no matter how horrific the situation in each building, not one person thinks to leave. In High-Rise and Shivers, their micronational dystopia is preferable to the banality of the outside world.

Before Wheatley arrived, if you knew of Ballard’s book and you saw the opening sequence from Shivers, you’d be forgiven for thinking you were about to watch Cronenberg adapt High-Rise. In fact, the correspondences with the novel throughout the entire film are so remarkable, some believe he must have read High-Rise before he made Shivers. However, he wrote the script at the same time as Ballard wrote the book, and both film and novel were released around the same time in 1975. It is simply one of those uncanny occurrences where two artists are in telepathic symbiosis, tapping the zeitgeist at exactly the same time.

Wheatley understands this. Think of his High-Rise trailer, then, as not just an adaptation of Ballard, but also a homage to Cronenberg.

What more could any hardcore Ballardian want?

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.